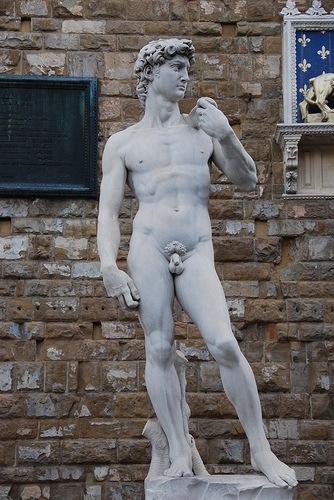

Michelangelo’s David, which for centuries guarded the entrance to Florence’s town hall, is the world’s greatest work of public art. It is also a flawed work of art. The hands are distortedly large; the neck is as long as the face; the vast triangle between the legs is too empty. Most glaringly, the gigantic statue fails to communicate the essential fact of the biblical giant-killer’s diminutive size.

These flaws are not due to any failures in Michelangelo’s conception or execution, but simply due to David never being designed for such a role in such a position. The statue was designed to be placed on the cathedral’s roofline and thus to be seen from far below, from which distance and distorted perspective the ‘flaws’ would have been necessary compensations; it was also designed to be seen as merely one biblical hero among many.

Yet upon its completion the statue’s planned resting place was disregarded, and instead David was seized upon as the unique and perfect symbol of Florence’s independence and ability to defeat its enemies, and this explains its placing beside the city’s seat of government. It is said that following the statue’s installation Florentines spontaneously festooned the statue with pieces of paper praising it as embodying the spirit of Florence.

There lies a story in what drove the Florentines to do this, one which raises questions about the role of public art, and more broadly urban planning, in defining and representing a culture.

The unified cultural acceptance of David upon its installation in 1504 was rare in Florence. The city’s culture had been so riven with contradiction that at the same time as the elite inspiringly hymned the Perfectibility Of Man and the Rebirth Of Civilisation the fiery preachings of the apocalyptic monk Savonarola throbbed in the ears of the poor. Shortly after the death of the death of the urbane philosopher-king Lorenzo de Medici, Savonarola swept to power with a mandate to purge Florence of what he saw as the heathen depravity of the elite’s culture.

This purge most famously included the Bonfire of the Vanities, before a precipitous fall from grace saw the monk executed as a heretic in 1498. This cultural conflict is one of history’s most extreme examples of a conflict that is a fairly common aspect of urban planning decisions: highly stratified societies tend to fail to produce unified cultures, and deciding which culture should be codified into the design of the area is a politically fraught one. There is also a danger that the process will be dominated by those with greater disposable income, not because the poorer people are somehow uncultured but because producing something to symbolise the way they live their lives is more likely to be seen by them as ‘gilding the lily’ — and perhaps with their tax money, to boot.

In Florence, the division was so profound, the potential backlash so great, that the buildings the elite built for themselves typically undermined, rather than codified, their culture; they built not optimistic symbols of human perfectibility but fortress-like urban palazzos to retreat into.

Against this background of cultural conflict the unified cultural acceptance of David is striking. Was it due to the biblical figure’s classical-style statue serving as a cultural compromise: a godly hero of heathen grace? Perhaps, in part. Surely more important, however, are events that happened in the Italian peninsula during Savonarola’s brief reign.

In 1494 an expeditionary force under the personal command of Charles VIII of France invaded the peninsula on the pretext of Charles’ claim to the throne of Naples. The contemptuous ease and unaccustomed brutality of his progress through the richest, most cultured and most militarily sophisticated land in Europe shocked Italians. If Charles could so humiliate Italian armies, which other kings might invade in search of such rich, easy pickings? Italy’s notoriously fractious city-states united around these aims: Charles must be stopped and Charles must be punished. The Italian alliance would cut off Charles’ supply lines and force his weary, discontented and syphilis-ridden army of 9,500 to march towards the Italians’ 30,000 fresh and well-prepared troops at the place of Italian choosing.

At Fornovo the armies clashed. The Italians’ intricate strategy foundered on unexpectedly sodden ground; the strategy’s inventor had flung himself into the heart of the battle in a bid for personal glory, and could not communicate a back-up plan. The Italian alliance fractured into its constituent armies, each doing what it thought best. The French army breached the Italian lines and escaped.

The consequence of this disaster was that all the kings of Europe knew how vulnerable Italy, with its weak, uneasy alliances and ‘laughably civilised’ etiquette of warfare, really was. For the next three decades, culminating in the Sack of Rome in 1527, Austrian, Burgundian, Flemish, French, German, Hungarian, Spanish, Swiss and other armies invaded the Italian peninsula in unending waves of massacre, rape, desecration, arson and looting that no Italian state or alliance could hope to repel.

In his classic book The Italians, Luigi Barzini described the significance of the Battle of Fornovo for the psyche of his defeated compatriots. It seemed to show:

“the world the impotence of a great nation, the immense booty which could be gathered with little danger, the passive weakness of the over-civilised inhabitants, their incapacity to work in cohesive and coherent bodies, their readiness to resign themselves pliantly to the ways of rough, brutal and resolute invaders. The ruin and humiliation of great peoples, … proud of their achievements, fanned nationalism, a hidden hatred of the foreigners, so obviously inferior to the natives in culture, savoir faire and the arts, a xenophobia without which many succeeding events could not be easily explained. It sporadically burst out in savage and bloody revolts, followed by periods of supine and servile resignation.”

The template for the Renaissance ideal, the universal genius Leon Battista Alberti, had inspired this generation with the motto “a man can do all things if he but wills them”. How hollow that must now have sounded. How shattering the realisation that this most brilliant, most individualistic, most strong-willed of generations could be contemptuously thrashed by almost any army that so desired precisely because they were too individualistic and strong-willed to work together cohesively.

In the years after the Sack of Rome many Italians would reject the intellectual daring, individualism and wilfulness of the Renaissance; the Counter-Reformation saw a firm reassertion of orthodoxy and tradition, a refusal to debate or compromise, a prohibition of books and an intolerance of heresy. The spirit of free inquiry turned into the spirit of the Inquisition. Instead of the Renaissance ideal of fully-developed, multifaceted and independent individuals, many of the best and brightest now submitted themselves to the military discipline of the Jesuit order, which demanded that its recruits have no more will of their own than that of ‘an old man’s walking stick’or that of ‘a corpse’; or else they performed spiritual exercises in the hope of obliterating individuality during mystical unions with God.

By 1571 the organisational power and new sense of common purpose of the Catholic Church was influential enough that the Pope was able to broker an alliance of Italian states and Spain named ‘The Holy League.’ At the Battle of Lepanto the League not only defeated the hitherto invincible Ottoman Empire, it turned back the Empire’s westward expansion, saved the Italian peninsula from potential invasion and forever broke the back of Ottoman seapower. Although, in a sign of how much culture had changed since the Renaissance, the League credited the Virgin Mary’s intercession for the victory, surely the successful demonstration of Italian cohesiveness also laid to rest some appalling humiliations. The Italian peninsula ceased to be seen as ‘the natural battleground of Europe’; the tiny, fragmented states of Germany now took up the horrors of the role. Italy had recovered her pride, but the daring individual brilliance of its Renaissance was forever gone.

But in 1504 all this was still in the future; in Florence — no matter how powerful her enemies — no-one was ready to give up on the Renaissance’s glory and its dream. And in all the Bible who is a more glorious and improbable military victor — and who a greater individualist — than the sculpted character being wheeled through the city’s streets towards its city hall?

In the context of the incessant invasions of Italy, Florentines’ cultural unity over Michelangelo’s giant David as a symbol of Florence’s independence and ability to defeat its enemies becomes clearer, and more painful. It is difficult to see the statue and not be awed by its power; it is also difficult to see this Goliath-sized representation of the Bible’s diminutive giant-killer and not think ‘if this is their David, how vast, how terrifying, how powerful must their Goliath have been?’ Establishing this sculpture as the symbol of Florentine independence was an act of defiance, certainly; but surely also a despairing admission that their life as an independent state was nearing its end. A common desire for Florence’s built environment to embody a shared culture had been born, but only when that culture was seen as being under mortal threat; the republic of Florence’s citizens only became conscious of what they shared when the republic was dying. ‘The owl of Minerva’, in Hegel’s phrase, ‘spreads its wings only at the falling of the dusk’.

Few situations are as dramatic, few cultural conflicts so extreme, as that which preceded the unveiling of the world’s greatest piece of public art. Are there, then, any urban planning lessons to be drawn from this history? Naturally, all sites must be looked at on their own terms, but there seem to be several implications worth drawing out.

Firstly, and perhaps rather uncontroversially, urban planning decisions are far easier when the society is not highly stratified, as there is less opportunity for different cultures to develop in isolation from, and in opposition to, each other. Whilst much of how to achieve this lies beyond the ambit of urban planning, planners too have their contributions to avoiding such a situation, for example in making provision for a wide mix of people to live in the same area, to plan so as to avoid dependence on expensive modes of transportation to fully engage in public life, and to avoid dividing neighbourhoods in two through the intrusion of impermeable barriers such as urban motorways or train lines.

Secondly, a culture sufficiently conscious of itself to be capable of culturally representing itself in defining works of art, literature etc. has already started to formalise the structure of that culture, and fix its limits. Presuming that every culture is not wholly unified but possesses structural tensions, then the formal recognition of the character of the culture consequently also formalises these tensions. Such tensions thus clearly become a potential target for criticism, and those deemed outside the culture’s limits become a potential pool of critics of that culture. A culture sufficiently conscious of itself to want to codify itself in the design of the built environment may then, already have peaked and be on the path to being replaced by a very contrary culture. (Indeed, as in the case of Florence, it may be the very mortality of the culture that is driving the desire for its immortalisation in the built environment.) Therefore, whilst it may be inspiring to work on urban design projects on behalf of a community with a coherent vision of itself, also take time to identify internal tensions in that vision, and talk to those who live lives beyond the limits of that culture. Work on achieving the vision, but, in designing, also whilst designing also consider that the dominance of cultures may be fleeting, and that generations often revolt against the culture they grew up with. Our work should not only serve the culture of today, but should span generations.

Thirdly, planning projects may take years from conception to completion and, like Michelangelo’s cathedral roofline enhancement project, may be completed in social and economic circumstances vastly different to those that accompanied their beginnings. During and after recessions, forlorn, half-completed construction projects may become a feature of many landscapes, and projects once seen as ‘aspirational’ may be considered ‘symbols of excess’ under the influence of newly-powerful opponents of that culture. Yet history shows many examples of the styles of one period having been bitterly attacked by the succeeding generation yet now beloved by those remote in time, context and place. There is no way to determine in advance which styles will one day be admired and which will attract no interest, but I suggest that a helpful test is through seeking out not only those who share the place’s vision, nor only those who live outside its limits in potential opposition to it, but also a range of those who have no connection to the place or its culture, and seeing if to them, too, our plan has a grain of appeal. Whilst building on existing culture is a vital part of the planning process, the demographic changes of urban areas can be vast and swift, and so we need to keep in mind that future inhabitants of the place may have little in common with those on behalf of whom we labour.

Lastly, though seeing a project through to completion requires the winning of many battles, we should bear in mind that without sufficient goodwill even the greatest accomplishments can be swiftly destroyed, and the most utopian of projects may swiftly become sink estate no-go areas. For without sufficient goodwill towards a place, budgets to maintain it form a tempting victim for spending cuts. It is therefore important to turn no opponent into an enemy; turn no shared, public space into the exclusive playground of a privileged few; and turn no celebration of a culture into a triumphal sneer. After all, there isn’t only David but also Ozymandias.